Most of us are familiar with bluebird and wood duck boxes, purple martin, bat and mallard hen houses, and maybe even bee condos and bee hotels.

But chimney swift towers?

That one was new to me when this past winter I read Boy Scout Sam Taylor’s Eagle Scout Service Project in the Story County Partners’ newsletter.

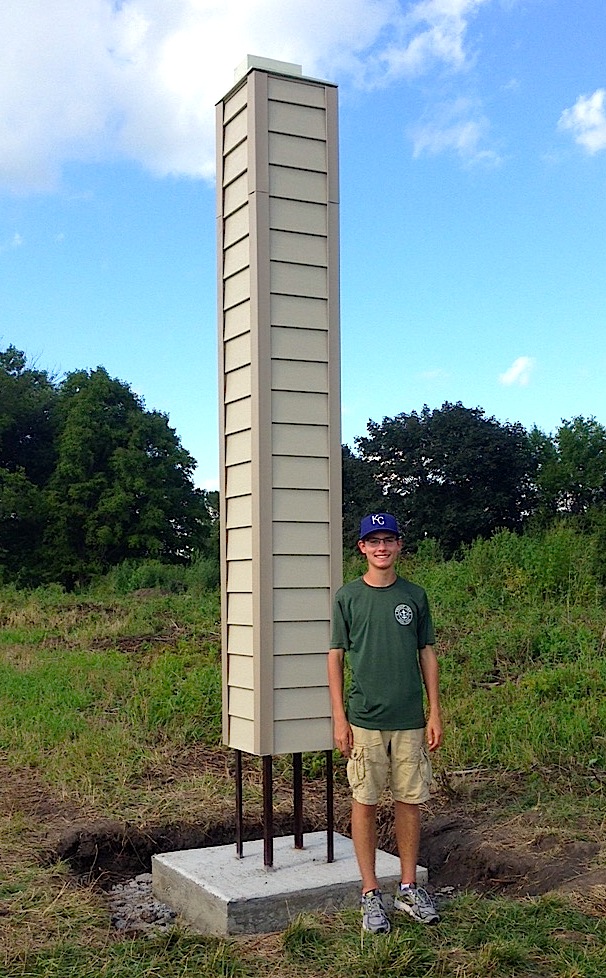

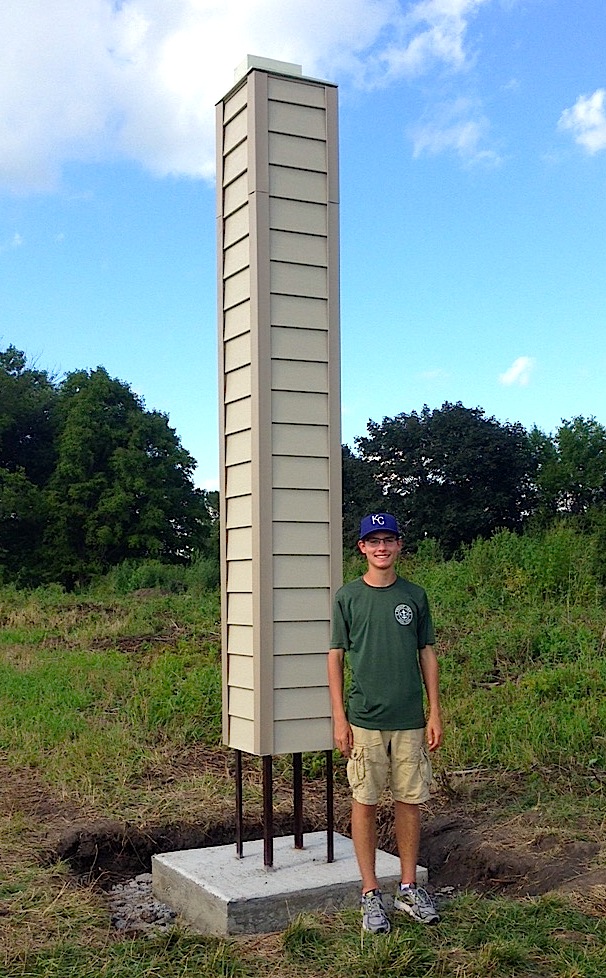

Taylor, a 16-year-old sophomore at Ames High School, chose to construct a chimney swift tower after being presented a list of possible projects from staff at Story County Conservation. With the help of other Scouts, adult leaders and his parents, he completed the project last fall by Dakins Lake near Zearing and recently had his Eagle Award ceremony.

While chimney swift roosting towers might be unfamiliar to some of us, prior to taking on the project Taylor didn’t even know of the existence of chimney swifts, a member of the swallow family.

“They sent me a list of projects, and I just thought this one looked interesting,” Taylor said. “So I started doing some research and got the book “Chimney Swift Towers: New Habitat for America’s Mysterious Birds,” which had the plans for the tower. I also communicated with the authors (Paul and Georgean Kyle) to get some ideas from them.”

Erica Place, outreach coordinator for Story County Conservation, said staff members are always on the lookout for new features to add to the county’s park system.

“The idea came about when we learned that a Boy Scout constructed a tower of similar design at Jester Park as his Eagle Scout Service Project in 2015,” she said. “I regularly ask our staff for Eagle Scout Project ideas, and (Natural Resource Specialist) Amy (Yoakum) suggested we add this to our list of potential projects. It wasn’t on the list long before Sam grabbed it.”

There are different designs for chimney swift towers, and Taylor settled on a three-box-affixed, 12-foot-tall tower with vinyl siding that is anchored to a concrete slab. The tower could potentially hold up to about 100 roosting and nesting birds.

“We originally thought of putting it at McFarland Park but then decided it wasn’t close enough to a town,” Taylor said. “We decided on Dakins Lake just outside of Zearing thinking the birds were more likely to come to the town and then find the tower.”

Steve Dinsmore, professor in the Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management at Iowa State University, said chimney swift tower construction, while not new, is a growing bird conservation practice.

“This is becoming more popular as we recognize that swifts continue to decline,” he said. “I do think they are effective, but most probably only house a small number of pairs.”

Historically, chimney swifts migrated to the United States from their winter homes in Peru and spent the nesting season in the more heavily forested eastern half of the country and rarely were seen west of the Mississippi River. However, as forests were cleared, swifts began adapting their nesting and roosting habits to include chimneys and smoke stacks. As a result, their range expanded and now extends from the East Coast to the Rocky Mountains, according to the Chimney Swift Conservation Association.

However, since the mid-1960s, chimney swift numbers have been in decline, primarily due to the loss of habitat in the form of large old building structures being demolished. Chimneys in newly constructed buildings are typically made from metal, which is unsuitable to swifts because it is too slippery for them to cling to as well as for their nests.

This is where a pioneering Iowa ornithologist and Taylor’s project converge.

In 1915, Althea Rosina Sherman, a writer and illustrator born in National, Iowa, hired carpenters to build a 28-foot-tall, 9-foot-square wooden tower, from her own designs, to attract and observe nesting chimney swifts. For nearly two decades she researched swifts, but after her death the tower was moved and fell into disrepair.

In recent years, though, interest in Sherman and her research has grown and after years of planning and fundraising, the original tower was restored and placed on a preserve near Buchanan, Iowa, where it is being used to educate people on chimney swift conservation, which includes building towers, such as the one Taylor constructed.

“I haven’t been out to check it this spring,” Taylor said. “But hopefully the chimney swifts will find it and use it.”

To learn more about Althea Rosina Sherman, visit www.althearsherman.org.

A swift half

Want to know more about chimney swifts and how you can help them? You can, says Steve Dinsmore, professor in the Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management at Iowa State University.

“Many states now have formal chimney swift surveys in place, mostly at known towers and also at known roosts during fall migration,” Dinsmore said. These are citizen science projects.”

To learn more about a group that sponsors “A Swift Night Out” as part of these efforts, visit www.chimneyswifts.org.

Todd Burras can be reached at ou****************@***il.com.

Entry Point No. 16 Moose River North — A windfall balsam may block the progress of a vehicle, but it cannot impede a spirit called into the wilderness. A raven croaks. A robin sings. A time-worn portage trail is covered by snow, ice, water, leaves, mud, tracks. Whitetail. Wolf. Moose River North droning in the distance … always, hypnotic in its invitation. That is until the thunder of ruffed grouse wings momentarily breaks the reverie. A new song. A new season. Nothing will hinder the desire of the water to rush on toward Hudson Bay. Nothing can halt the march of spring into the North Country.

Entry Point No. 16 Moose River North — A windfall balsam may block the progress of a vehicle, but it cannot impede a spirit called into the wilderness. A raven croaks. A robin sings. A time-worn portage trail is covered by snow, ice, water, leaves, mud, tracks. Whitetail. Wolf. Moose River North droning in the distance … always, hypnotic in its invitation. That is until the thunder of ruffed grouse wings momentarily breaks the reverie. A new song. A new season. Nothing will hinder the desire of the water to rush on toward Hudson Bay. Nothing can halt the march of spring into the North Country.